Gender Aspects in Humanitarian Sanitation and Faecal Sludge Management (FSM)

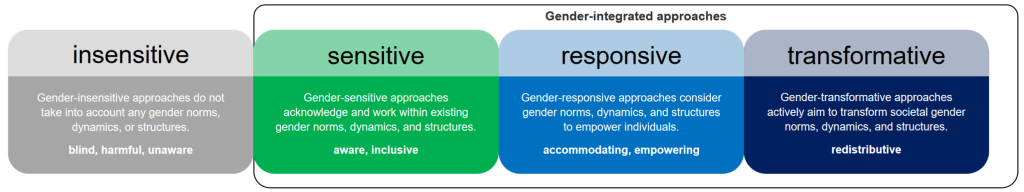

Humanitarian crises affect girls, boys, women, men, and people with diverse SOGIESC differently. This topic sheet is designed to enhance gender equality in sanitation and Faecal Sludge Management (FSM) during emergencies. This resource provides a concise overview of approaches for gender integration in humanitarian sanitation projects, ranging from gender-sensitive to gender-responsive and ultimately gender-transformative. This sheet is accompanied by a checklist that contains more specific suggestions and recommendations for promoting gender equality in humanitarian sanitation and FSM projects.

Advancing gender equality in sanitation and FSM requires actions at 4 interconnected levels of practice:

Individual sanitation practitioners: Effective sanitation programming requires a personal commitment to gender equality from individual sanitation practitioners. Self-assessments, like Water for Women’s example, encourage people to reflect on their own biases and discriminatory attitudes, while training programs can help them learn how to address harmful gender beliefs and avoid perpetuating stereotypes.

Organisational: Historically, men have held a majority of positions in the humanitarian sector and WASH response. Humanitarian organisations should apply gender-transformative principles to their own internal practices. To address deeply ingrained gender stereotypes in humanitarian roles, organizations need models and leadership that support better gender balance in policies, strategies, programs, standards, guidelines, and the hiring and promotion of more women and minority sanitation professionals.

Programme: Gender equality and women’s empowerment should be central to programme design and budgeted for from the start. To ensure transformative outcomes, sanitation facilities and FSM services should be designed with gender analysis and monitoring, and accountability mechanisms should be implemented. Using collaborative planning processes, like WASH committees, can help everyone be involved in planning, monitoring, and maintenance. Working with gender equality groups can help us understand the complex issues around gender norms and roles in sanitation, empowering communities to develop their own strategies for equality using participatory methods.

Setting: Long-term humanitarian sanitation and FSM interventions can serve as a way to challenge gender norms in hygiene and sanitation, addressing the underlying causes of gender inequality. This requires a transfer of power and resources to actors in the affected contexts and communities, especially to women-led civil society and gender equality movements.

Safe, private, and accessible sanitation services, including latrines for managing menstrual hygiene and incontinence, and catering to the needs of caregivers, are a fundamental human right, even during emergencies. Despite the importance of women’s voices, social norms and gender roles often hinder women’s participation in decision-making, which can result in their needs being overlooked, especially those who are older, disabled, or from minority groups (Kumar et al, 2023). Focusing on technical solutions without considering gender differences can restrict access to essential services like sanitation, making gender inequality worse. Conversely, humanitarian sanitation and FSM initiatives can advance gender equality by fostering a more balanced sanitation workforce, guaranteeing equal access to sanitation services, enabling participation in sanitation-related decision-making, and redistributing domestic WASH responsibilities within households.

Approaches for gender integration in humanitarian sanitation and FSM span a continuum from gender sensitive, gender responsive to gender transformative aspects. The availability of opportunities for gender equality in humanitarian work is often determined by the phase of the emergency and the specific situation. Humanitarian sanitation actors must take action on multiple levels before, during, and after emergencies. Addressing staff mindsets and organizational change is crucial in preparation for the response. Basic sanitation needs take top priority in the first response phase, particularly during rapid onset emergencies. The range of options for gender-responsive WASH programming generally increases in later phases of humanitarian response or during longer-term interventions. The move from humanitarian to development programmes and integrated change processes (such as the humanitarian-development-peace nexus) provide the opportunity for gender transformative approaches, given the extended timeframe and sustained organizational presence.

Source: MacArthur et al., 2023

Insensitive programming: Insensitive programming is evident in sanitation facilities that lack gender separation and are installed in distant, often isolated and unprotected areas. This poses a challenge for women and girls, people with disabilities, children, and the elderly and elevates the risk of sexual violence. Gender insensitivie programmes can unintentionally strengthen negative gender expectations by relying on the unpaid or poorly compensated labour from women in areas like sanitation promotion and caregiving.

Inclusive sanitation in Cox’s Bazar: Key principles of the sector strategy

The WASH Sector identified four guiding principles to promote a more inclusive strategy:

1. Put gender and inclusion at the centre of the Government and WASH Sector’s interventions by recognising that different people face different barriers to exercise their equal rights to live in safety and with dignity

2. Listen to and consult with recognised groups such as representatives of the community (women or disabled persons)

3. Prioritise those who face most difficulties in fulfilling their WASH needs

4. Improve effectiveness through increasing knowledge, capacity, commitment and confidence

Source: Kurkowska, M. et al (2019) Dignifying sanitation services for the Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar camps Rural 21

Sensitive programming To address immediate survival needs, sensitive programming prioritizes equitable access to sanitation services for girls, boys, women, men, and people with diverse SOGIESC. Programmes focus on the design of gender-sensitive sanitation technologies. As an illustration, in Somalia, CARE’s WASH team worked alongside women and girls to develop latrine designs tailored to women’s specific requirements (Sheikh, 2022).

Moving from gender sensitive to gender responsive sanitation: Oxfam’s Sani Tweaks project

SaniTweaks advocates for ‘good enough’ sanitation as a priority during the first stage of first phase/rapid onset emergencies. By incorporating insights from extensive consultations, including an understanding of power dynamics, social preferences, and coping mechanisms, quality standards can be refined and improved, leading to ‘tweaks’ or adjustments in designs, materials, maintenance, and usage models. Latrine use, especially by women and girls, can be increased by addressing their specific needs, including safety, privacy, accessibility, and menstrual hygiene management.

Source: https://www.elrha.org/project/sani-tweaks-diffusion-for-maximum-impact-at-scale/

Responsive programming: Gender-responsive programming can empower women to speak about their sanitation needs and work together to find solutions. Activities focus on empowering communities and households to participate in sanitation and FSM planning, maintenance, and decision-making, ensuring gender equality in WASH committee membership and leadership. By including diverse women in the sanitation workforce, gender-responsive models aim to foster decent work opportunities and income-generating possibilities for women. Training women in every sanitation job—from cleaners to engineers—would challenge gender norms, create more opportunities for women, and boost local sanitation services. View this chart for examples that show how women currently participate in the humanitarian sanitation value chain.

Gender gaps in the WASH sector, South Sudan

IOM and RedR UK performed the first Cluster-wide study in South Sudan to examine the gender gap in women’s participation in the WASH sector. The findings show that at:

• Leadership level: there are over triple the number of male managerial staff when compared to female

• Technical level: no women staff within the engineering programmes

• Community level: there are 33 per cent more volunteers who are women when compared to men

Community attitudes, familial pressure, household responsibilities, violence, and lack of education all impede women’s involvement in WASH. The study reveals how institutionalized inequalities in recruitment, job classification, pay, and benefits systems limit women’s opportunities and rights in the workforce.

Source: Kate Denman and Leigh-Ashley Lipscomb (2020) Closing the Gender Gap in the Humanitarian WASH Sector in South Sudan IOM

Transformative programming: There’s ongoing discussion in the humanitarian sector about the possibility of incorporating gender transformative practices into every humanitarian response and setting. While gender-sensitive practices are anticipated in the early stages, gender-responsive actions are expected in the mid-term, and gender-transformative programs are envisioned for the long term, a path towards gender-transformative change can be pursued throughout all phases of humanitarian WASH if it’s based on gender analysis and includes risk mitigation. In humanitarian situations, organizations such as Plan International, Oxfam, and CARE have recognized men as key players in creating positive change by involving them in efforts to reduce stigma surrounding menstrual health and hygiene, promoting equitable division of domestic WASH responsibilities, and implementing programs like ‘Dad’s Magic Hands’ to address gender stereotypes and encourage men’s participation in shifting traditional gender roles.

Women Lead in Emergencies model

The Women Lead model consists of 5 steps designed to help women in conflict-affected communities advocate for their rights and contribute to emergency preparedness, response, and recovery. The project in Uganda trained and sensitized “Role Model Men” on gender equality issues. One role model man described how a cultural exchange with other Women Lead groups had helped him question his own social norms: “In Kyangwali we were taken and observed that men there fetch water for their homes, which was different from in our culture, where a man can’t fetch water. Right now, I fetch water, even sweeping the compound, I do all. My mindset was completely transformed to be more supporting. (FGD Role Model Men, Ariaze A – Rhino Settlement, Arua, Uganda)”

Source: Luisa Dietrich (2022) Women Lead In Emergencies Global Learning Evaluation Report CARE International UK

-

Bibliography

Women and Girls Centered Latrine Co-creation Approach to Increase Acceptability and Optimise Use of Shared Household Latrines in Somalia

Oxfam Sani Tweaks - Best Practices in Sanitation

Female-Friendly Public and Community Toilets - A Guide for Planners and Decision-Makers

Closing the Gender Gap in the Humanitarian Wash Sector in South Sudan

Women Lead in Emergencies Global Learning Evaluation Report

Dignifying Sanitation Services for the Rohingya Refugees in Cox’s Bazar Camps

Gender Equality Approaches in Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Programs: Towards Gender-Transformative Practice

Key Resources and Tools

Checklist for Integrating Gender Equality in Humanitarian Sanitation and Faecal Sludge Management (FSM)

The checklist for integrating gender equality into humanitarian sanitation and faecal sludge management (FSM) highlights…

Agora Gender-Responsive Programming on Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Playlist

This learning playlist aims to provide UNICEF staff, implementing partners and consultants with tools and…

IASC Gender With Age Marker

The IASC Gender with Age Marker (GAM) helps users to design and implement inclusive programs…

Strengthening Gender Integration in Sanitation Programming and Policy: Insights From Literature and Practice

Gender equality and inclusion are key aspects of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) service provision…

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Self-Assessment Tool

This guidance is for staff of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) implementation and research projectsand…

“They Know What We Don’t:” Meaningful Inclusion of LGBTIQ People in Humanitarian Action

This report explores how the humanitarian system is responding to the needs of lesbian, gay,bisexual,…

Gender in Wash Humanitarian Response Checklist for Humanitarian Actors

This checklist has been produced to assist humanitarian workers self-assess the extent gender concerns are…

Integrating Gender Equality Into Community Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Projects - Guidance Notes

Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and gender equality are often treated as separate thematic areas,…

Accessibility and Safety Audits

Accessibility and safety audits are participatory and practical tools that can be used to rapidly…

Rapid Gender Analysis

Gender analysis is the systematic attempt to identify key issues contributing to gender inequalities, many…

WASH Safety and Accessibility Toolbox

This toolkit is designed to provide practical monitoring mechanisms to track the quality and safety…

Monitoring Menstrual Hygiene Management Programming in Emergencies - A Rapid Assessmenttool (M-Rat)

This Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) Rapid Assessment Tool (M-RAT) is designed toassist the humanitarian community…

Oxfam Gender in Emergency Standard

Oxfam’s 2022 Gender in Emergencies (GiE) Standards are the key internal tool by which we…

Examples of Engaging Women Along the Humanitarian Sanitation Value Chain

Found what you were looking for?

Still have questions?

You could not find the information you were looking for? Please contact our helpdesk team of experts for direct and individual support.