The Saniforce, a Solar Thermal Pasteurizer, for wastewater disinfection and cholera prevention in humanitarian settings

Description of the emergency context

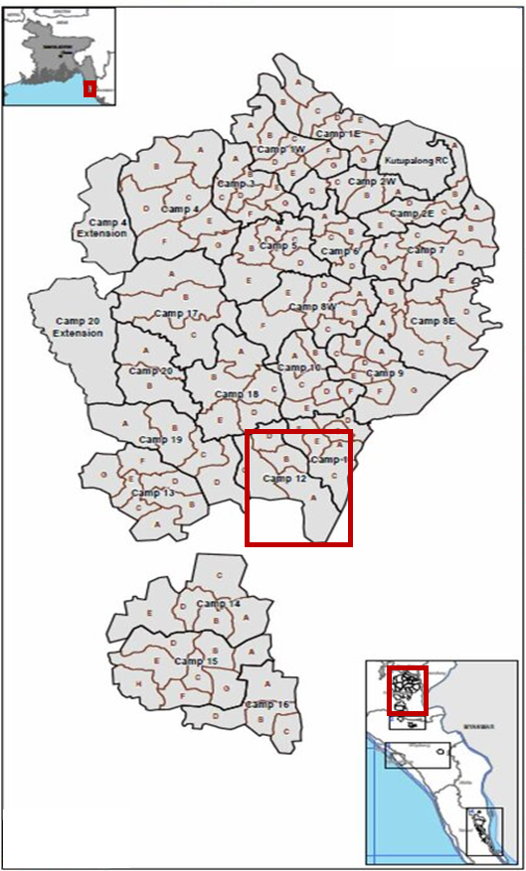

The Rohingya, an ethnic minority from Myanmar, have faced decades of discrimination, restricted rights, and violent crackdowns, particularly after the 1962 military coup. The latest escalation in August 2017 forced nearly one million Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. The Government of Bangladesh established large refugee settlements across the hilly areas of Cox’s Bazar (Ukhia and Teknaf), which by June 2023 hosted over 1.1 million people. In such mass-displacement settings, effective faecal sludge management (FSM) is essential to protect public health and reduce environmental contamination.

Numerous national and international organisations are responsible for faecal sludge management (FSM) in the camps. As of 2023, the Cox’s Bazar WASH Cluster reported approximately 49,530 latrines, serving an average of 21 people per latrine. This results in an estimated sludge generation of 1.1 L/person/day—equivalent to roughly 1,025 m³ of faecal sludge per day (1.5–2% solids). In parallel, 164 faecal sludge treatment plants operate in the camps with a combined treatment capacity of 879 m³/day, which remains insufficient to treat the total daily sludge production (data sourced from the FSM Strategy for Cox’s Bazar, August 2023, available at: https://rohingyaresponse.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/FSM-strategy-Final-Version-CXB-August-2023.pdf).

Extreme population density, limited land availability, constrained technical capacity, and exposure to climate hazards (including frequent flooding and landslides) make WASH service provision exceptionally challenging in the Rohingya camps. These vulnerabilities can lead to cholera outbreaks, which continue to pose a persistent threat to the local community. In this context, robust, resilient and easy-to-operate technologies are needed to safeguard public health. The solar thermal pasteuriser (STP) Saniforce, developed by the Veolia Foundation, offers a promising solution that utilises solar energy to inactivate pathogens without the use of chemicals.

A pilot unit was deployed at the decentralised wastewater treatment system (DEWATS) in Camp 12 to assess its ability to fully inactivate pathogens as a post‑treatment step. The objective is to generate evidence on treatment effectiveness and evaluate its suitability for replication in other humanitarian contexts. By ensuring complete pathogen inactivation, the STP contributes to cholera prevention and reinforces infection‑prevention and control measures in a setting highly vulnerable to rapid disease transmission.

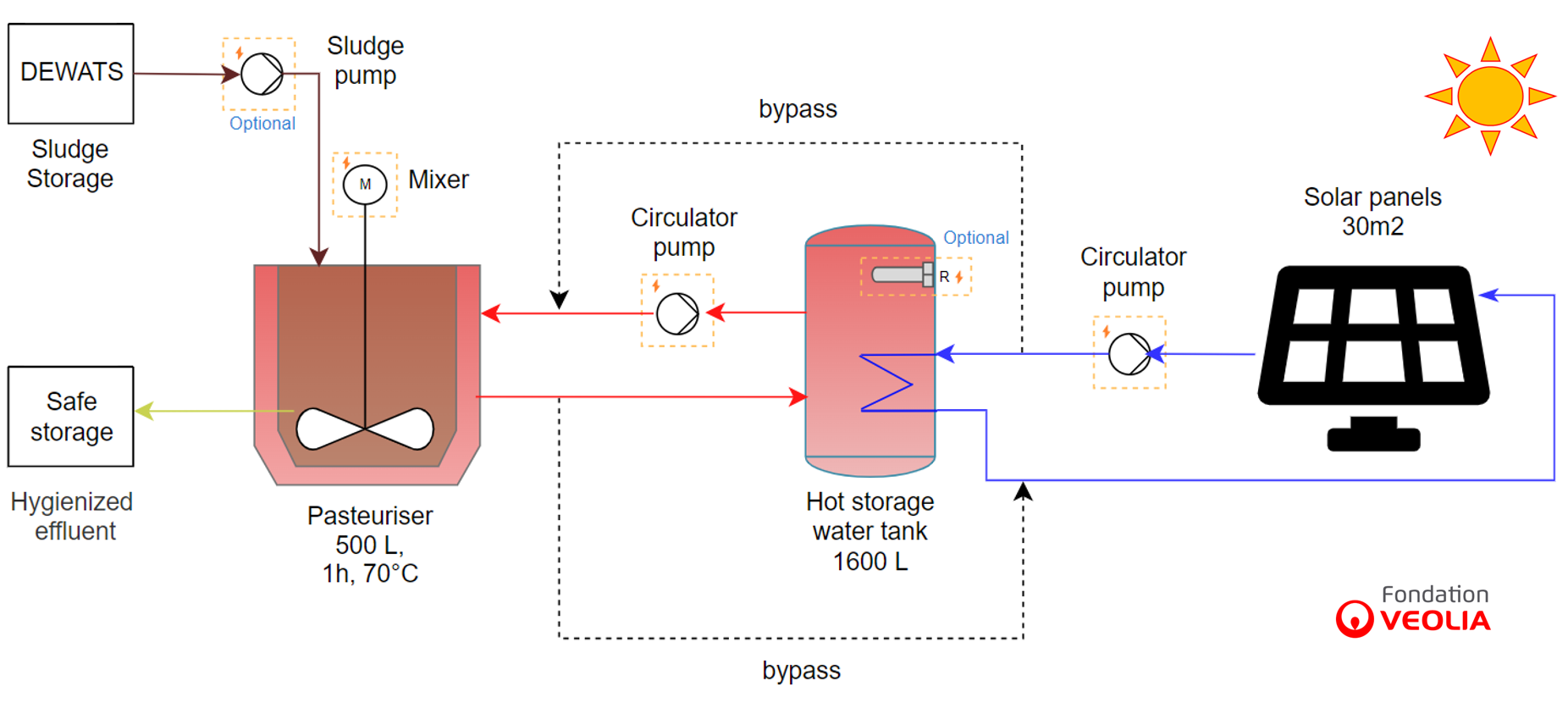

Pasteurisation takes place in a 500 L mechanically stirred, thermally insulated tank equipped with a double jacket. Operating in batch mode, the process gradually increases the temperature of the sludge until it reaches the pasteurisation setpoint. Once this temperature is achieved, active heating stops and the sludge is held at that temperature for the required retention time to ensure pathogen inactivation.

To stabilise performance and optimise the use of solar energy, the system includes two interconnected 800 L thermally insulated buffer tanks for storing excess heat. One of these tanks is equipped with a 3 kW electric resistance heater, which provides backup heating during periods of low solar radiation, such as cloudy days. The hot water circulation is flexible: it can flow from the solar collectors to the pasteurisation tank, from the collectors to the buffer tanks, and from the buffer tanks to the pasteurisation tank.

The solar pasteurisation system is modular and can be adjusted to match the required treatment capacity in different contexts. It can be upscaled by adding more solar thermal collectors and increasing the number and/or volume of the buffer and pasteurisation tanks. Conversely, it can be downscaled by using fewer collectors, and smaller buffer and pasteurization tanks.

The prototype itself was installed on flat, compacted soil adjacent to the DEWATS plant. For performance assessment, the DEWATS effluent was directed to the solar pasteuriser prototype. This stream had the appearance of a low-viscosity liquid (similar to water), with a strong odour, notable turbidity and visible suspended particles..

While the design and construction of the system require engineering skills, the unit is built in a workshop and delivered to site almost ready to use. Some expertise is still needed to install the solar thermal collectors and connect them to the pasteuriser. In contrast,, its day-to-day operation and maintenance are straightforward and do not demand specialised expertise. In case of technical issues, support from a local plumber or electrician is generally sufficient to restore functionality.

The site is exposed to heavy monsoon rains and flooding risks, but the technology has proven resilient thanks to its robust construction, corrosion-resistant materials, and heavy structural weight, which provide stability and protection under challenging weather conditions.

• Scalable technology (can be expanded or downsized depending on demand)

• Climate-resilient, with durable materials able to withstand extreme weather and a system capable of maintaining operation through stored thermal energy or backup power

• Low carbon footprint thanks to primary reliance on solar thermal energy

• Sustainable and energy-efficient system requiring minimal to low external power

• Replicable and adaptable to other humanitarian or low-resource settings

• Simple to operate and maintain, without the need for highly specialised skills

• Reduces health risks linked to contaminated effluent, especially during cholera outbreaks

• Requires sufficient space for installing the solar thermal collectors

• Limited performance during overcast or rainy conditions when relying solely on solar energy, making backup power necessary

• Challenging to reach and maintain temperatures above 70 °C’

• Unable to operate well with too viscous sludges

Final-report_Solar-Pasteuriser

Project Details

Engine

Water

FSM specialist for construction

Local NGO for operation and maintenance

Still have questions?

You could not find the information you were looking for? Please contact our helpdesk team of experts for direct and individual support.