Financing

Every humanitarian sanitation intervention requires financial resources to cover all the costs incurred by a sanitation project throughout the Humanitarian Programme Cycle. Financing must also take into account the cost of less tangible project components such as Capacity Development, Hygiene Promotion and Community Engagement Measures and administration as well as Operation and Maintenance requirements and the longer-term Sustainability of the sanitation system. There are several sources of funding for a humanitarian response with different funding mechanisms and types of donors; the appropriateness of the source will vary according to the context, urgency and the type of humanitarian organisation seeking funding.

-

- Estimate the funding required (Financial Planning and Budgeting) to implement the sanitation/WASH response planned by your organization

- Engage with development of joint plans with relevant humanitarian organizations such as the Humanitarian Response Plan (for example partnering with organizations working for shelter to develop a joint response plan addressing shelter and WASH response)

- Identify and select appropriate donors/funding sources for your organization based on donor funding mechanisms and their eligibility criteria. Please see some of the options below:

- UNOCHA – https://www.unocha.org/we-fund

- European Commission – https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/funding-evaluations/funding-humanitarian-aid_en

- 10 funding resources for humanitarian innovators complied by UNHCR – https://www.unhcr.org/innovation/10-funding-resources-for-humanitarian-innovators-2/

The need for humanitarian financing continues to increase, reaching an all-time high of around 3.2 billion USD for WASH globally in 2022. At the same time, the growth in financing has stalled and currently only meets about one quarter of WASH financing requirements (Humanitarian Funding Forecast, 2022).

Humanitarian agencies need to understand and engage with the various financing mechanisms and the eligibility/requirements of donors so that they can access adequate, timely humanitarian financing.

Each humanitarian sanitation intervention incurs costs arising from the technologies used along the entire sanitation service chain (including material and staff), its operation, maintenance and management as well as for accompanying measures such as capacity development, community engagement or awareness-raising and behavioural change activities. Costs are context specific.

Humanitarian financing can be defined as financial resources for humanitarian response to cover the cost of (1) saving lives, alleviating suffering and maintaining dignity during and after a crisis and (2) preventing and strengthening preparedness for a crisis, governed by humanitarian principles.

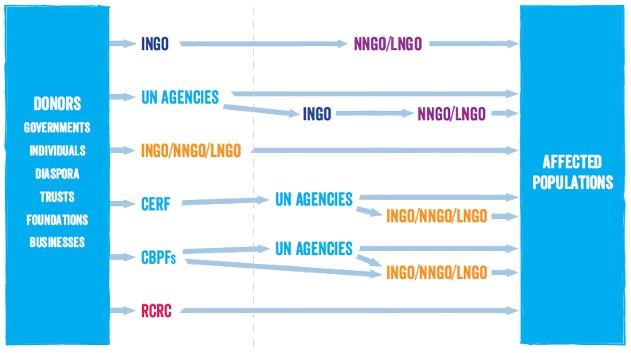

The diagram below illustrates some of the paths that humanitarian aid takes to reach the affected population.

INGO – International NGO; LNGO – Local NGO; NNGO – National NGO; CBPFs – Country Based Pooled Funds; CERF – Central Emergency Response Fund; RCRC – Red Cross/Red Crescent

Source: International Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA)

The biggest share of humanitarian financing is provided by larger donor countries, private donors or foundations, the wider diaspora of an affected country, multilateral donors or development banks and through pooled funds. UNICEF as WASH Cluster lead agency frequently manages larger chunks of funding which are often jointly implemented with local/international partners.

Government donors are the main source of international humanitarian funding. Over the past 10 years, the amount given by government donors has increased from 12.2 billion USD in 2012 to 24.9 billion USD in 2021; the majority of this (97%) has been provided by the largest 20 donor countries. However, the volumes given by individual governments have fluctuated over time. (Urquhart et al., 2022). Government donors provide humanitarian funding in different ways. Most funding is provided as bilateral contributions, with donors broadly or strictly specifying where and what their funding is spent on by the implementing organisations such as UN agencies and international NGOs. Governments also provide multilateral contributions for humanitarian responses in the form of core funding for multilateral institutions such as the EU and the UN. Most of the funding provided bilaterally by governments is channelled through multilateral organisations such as UN agencies (in the case of WASH usually UNICEF or UNHCR in refugee contexts), with a smaller proportion going to NGOs. However, there are some differences between donors.

Private donors provide significant contributions to international humanitarian assistance and are also a critical source of flexible funding for humanitarian organisations. Funding from private donors, including individuals, trusts and foundations, and companies and corporations, is generally less restrictive than funding from government donors. In 2019, 40% of humanitarian funding from trusts and foundations and 57% of funding from companies and corporations, was provided as unearmarked or softly earmarked funding, while nearly all the funding raised from individuals is unrestricted (Urquhart et al., 2022). Most individual giving is also not restricted to a certain timeframe, or, if donated to a specific appeal, is valid within the lifespan of that crisis. Overall, funding from private donors provides significantly more flexibility than funding provided by government donors and allows organisations to fund crises or projects that may be difficult to fundraise for through other channels, rather than being led by donor priorities. With different accountability structures to government donors, foundations and companies and corporations, private donors can be willing to fund projects that more traditional donors may not.

Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) have become increasingly active in crisis contexts. As the concentration of poverty in crisis-affected countries grows, MDBs are choosing to target a growing share of resources to these countries. This is through traditional MDB financing, as well as a growing number of crisis-focused instruments and tools. Support from MDBs to crisis contexts is primarily in the form of loans, with the aim of protecting social and economic development gains made by supplying long-term financing to governments and the private sector to support long-term recovery. The largest MDB donor to countries experiencing crisis is the World Bank’s International Development Association, followed by the Asian Development Bank and the African Development Fund (Urquhart et al., 2022).

Pooled funds were established in 2005 as the UN’s global emergency response fund. The Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) pools contributions from donors around the world into a single fund. CERF has a 1 billion USD annual funding target and is fully unearmarked to ensure funds meet the most urgent, life-saving needs. During emergencies, humanitarian organisations on the ground jointly assess and prioritise needs and apply for funding from the CERF. Funds are immediately released if these proposals meet CERF’s criteria, i.e. the needs are urgent and the proposed activities will save lives. CERF also has a 30 million USD loan facility to cover critical funding gaps in humanitarian operations based on indications that donor funding is forthcoming. CERF allocations are designed to complement other humanitarian funding sources such as Country-Based Pooled Funds (CBPFs) and bilateral funding. Whilst the CERF is directly accessible only by the UN, these agencies often partner with NGOs to implement CERF-funded activities. CBPFs are established by the UN Emergency Relief Coordinator when a new emergency occurs or when an existing humanitarian situation deteriorates. Contributions from donors are collected into single, unearmarked funds to support local humanitarian efforts. Funds are directly available to a wide range of relief partners CBPFs support the delivery of an agile response and encourage effective and efficient use of available resources. CBPF allocations are designed to complement other humanitarian funding sources, such as the CERF and bilateral funding.

It is to be noted that one of the commitments in the Grand Bargain states a target of at least 25% of humanitarian funding to local and national responders but is stagnating at around 2-3% of the total international humanitarian assistance.

Other types of financing can also be accessed e.g. climate finance or development financing for Disaster Risk Reduction, particularly for preparedness and building resilience.

-

Bibliography

Key Resources and Tools

Global Humanitarian Assistance Report

Overview of global humanitarian financing, tracking growth and need

Demystifying Humanitarian Financing

Series of webinars, videos and briefing papers to help NGOs better understand the various humanitarian…

Humanitarian Financing

Overview of financing instruments and mechanisms from UN OCHA

Related Topics

Still have questions?

You could not find the information you were looking for? Please contact our helpdesk team of experts for direct and individual support.